You’re receiving this message because your web browser

is no longer supported

We recommend upgrading your browser—simply click the button below and follow the instructions that will appear. Updating will allow you to accept Terms and Conditions, make online payments, read our itineraries, and view Dates and Prices.

To get the best experience on our website, please consider using:

- Chrome

- Microsoft Edge

- Firefox

- Safari (for Mac or iPad Devices)

peru

The story of Peru has been written over the ages by a number of ancient kingdoms—most notably the Inca, who left lofty Machu Picchu hiding high in the Andes for later explorers to puzzle over, but also other cultures, like the Nazca, who scratched thousand-foot geoglyphs into the southern deserts, and the Chimu, who built Chan Chan, the largest earthen city in pre-Columbian America. Modern Peru still holds many of the old traditions dear—for example curanderos, or shaman healers, can be found plying their trade in the countryside.

The country’s diverse history is matched by its variety of landscapes, each of which dazzle in their own unique way. In the Andean Highlands, you’ll trek under impossibly blue skies backdropped by snowcapped peaks; in the Amazon you’ll enjoy the company of exotic flora and fauna underneath a colorful rainforest canopy; and in sultry Lima you’ll find Spanish colonial architecture built along a beautiful Pacific coast.

Peru has elevated Latin cooking into an art, making expert use of local ingredients—for example, potatoes, tubers, corn, tropical Amazonian fruits, seafood, poultry, llama, and alpaca—while also gracefully fusing European, African, and Asian influences into its recipes. Peruvian culinarians famously invented ceviche, raw fished “cooked” in citrus juice. Whatever your tastes may be, Peru is sure to make an impression.

Your FREE Personalized Peru Travel Planning Guide

Your FREE Personalized Peru Travel Planning Guide is on its way

Want to continue learning about Peru? Return to our Peru destination page.

Go Back To PeruPlease note: To complete your registration, check your email—we sent you a link to create a password for your account. This link will expire in 24 hours.

Compare Our Adventures

Click 'Select to Compare' to see a side-by-side comparison of up to adventures below—including

activity level, pricing, traveler excellence rating, trip highlights, and more

Spend 12 days in Peru on

New! Peru’s Nazca Lines & Amazon Rain Forest

O.A.T. Adventure by Land

Spend 10 days in Peru on

Peru: Machu Picchu & the Sacred Valley

O.A.T. Adventure by Land

Spend 8 days in Peru on

Machu Picchu & the Galápagos

O.A.T. Adventure by Small Ship

Spend 5 days in Peru on our

Pre-trip Extension

Best of Peru: Lima, The Sacred Valley & Machu Picchu

Best of Peru: Lima, The Sacred Valley & Machu Picchu

Compare Adventures

Add Adventure

including international airfare

per day

*You must reserve the main trip to participate on this extension.

**This information is not currently available for this trip. Please check back soon.

You may compare up to Adventures at a time.

Would you like to compare your current selected trips?

Yes, View Adventure ComparisonPeru: Month-By-Month

There are pros and cons to visiting a destination during any time of the year. Find out what you can expect during your ideal travel time, from weather and climate, to holidays, festivals, and more.

Peru in January - February

January and February mark Peru’s wet season. You can expect rain at least once per day, and more in the lush, tropical climate of the Amazon Jungle. But the season’s showers usher in the bounty of Mother Nature: verdant, healthy vegetation blooms in the Sacred Valley, and frequent rainbows make this one of the best times to visit Cuzco. Trekkers hoping to hike the Inca Trail will find it closed for cleaning and maintenance, but Machu Picchu remains open throughout the wet season and plays host to gloriously few visitors.

This is also the best time of year to visit Peru’s stunning—and overlooked—beaches. The rains so common in the mountains and jungles are less frequent here, while temperatures along the coast remain high. And with fewer tourists to compete with, your travel dollar will go further.

Holidays & Events

- Early January: Three Kings Day

- Pisco Sour Day: The first Saturday of February is set aside to honor Peru's national drink

Must See

Carnival is celebrated across Peru with lively street parties, featuring water balloon fights. The end of the festivities is marked by the yunsa ritual, when a yunsa tree laden with gifts is brought to the festival. People dance around the tree, and couples compete to knock it down with an axe, releasing the gifts.

Watch this film to discover more about Peru

Peru in March - May

March, April, and May—Peru’s fall—usher in milder temperatures and the start of the dry season. The main tourist season hasn’t yet begun, so you can expect fewer crowds at Peru’s many ancient ruins and must-see sites. These are some of the best months to visit Machu Picchu—and if you do, you’ll witness the additional delight of orchids in bloom, which carpet the Sacred Valley and are visible on the train ride from Cuzco to Machu Picchu.

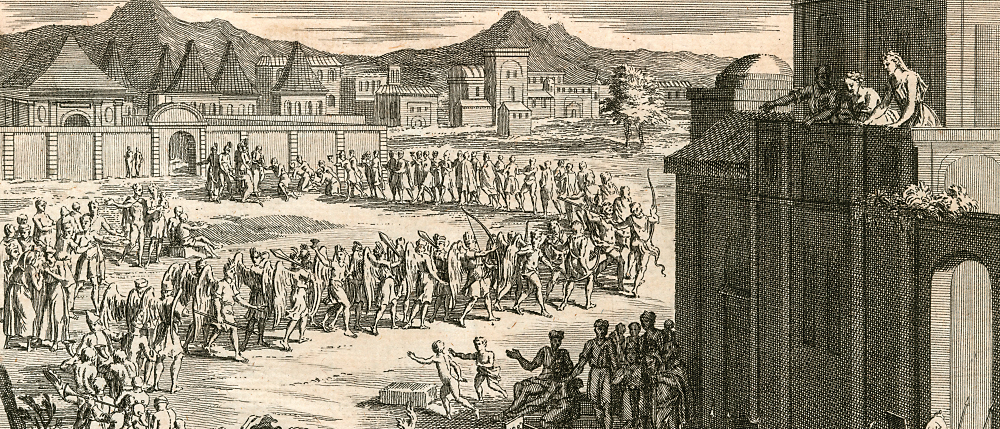

Peruvians’ religious beliefs are a blend of native animist traditions and the Roman Catholicism brought over by Spanish colonists, but Catholicism reigns during the Easter season. Depending on when Easter falls, much of March or April may be given over to religious celebrations. During Holy Week, expect the celebrations to kick into high gear, with religious processions occurring in cities and towns throughout the country.

Holidays & Events

- Early May: Feast day for Señor Muruhuay, who is renowned throughout Peru for his help in caring for the sick during a smallpox epidemic. In his honor, thousands of hopefuls embark on a pilgrimage or write a Carta a Dios, or Letter to God, asking for miracles or giving thanks for miracles already received. The Señor Muruhuay pilgrimage is considered one of the most important in Peru.

Watch this film to discover more about Peru

Peru in June - September

Peru’s winter months are the official peak of the dry season—and the tourist season. Drawn by cloudless skies, visitors flock to the mysterious ruins of Machu Picchu, which can see as many as 2,000 tourists a day. In the lowlands, few mosquitos and low humidity make this the best time of year to explore the Amazon basin, while in Lima, a dense fog known as La Garua blankets the city in a misty drizzle.

Despite Lima’s gloom, Peru’s winter months are the most popular time of year to visit, so it’s best to plan your visit in advance.

Holidays & Events

- May 1: Labor Day

- July 28-29: Fiestas Patrias. Peru’s national holidays are a two-day affair that celebrate the country’s independence from Spain in style: fireworks blaze across the night sky; the Gran Corso (Great Parade) dances through Lima with a trail of colorful floats, costumed performers, and marching bands; and Pisco sours flow freely from the nation’s watering holes.

Watch this film to discover more about Peru

Peru in October - December

October in Peru offers sunshine and mild temperatures, while late November heralds the start of the wet season. Despite the occasional downpour, December is still largely pleasant—and with less crowds to compete with, many travelers are willing to risk getting a little wet for a chance of uninterrupted time at Peru’s popular attractions.This is also an excellent time of year for viewing wildlife and birds—of the latter, Peru has more species than any nation except for Colombia.

Holidays & Events

- October 8: Battle of Angamos, which commemorates a naval battle fought between Peru and Chile during the War of the Pacific (1879-1883).

- November 1: All Saints’ Day

- December 8: Feast of the Immaculate Conception

Must See

Christmas Eve (December 24) is a festive event throughout this predominantly Catholic country, but in Cuzco, Santurantikuy Market is the place to be. The market is a riot of activity as shoppers buy last-minute presents, Andean vendors sell local plants and grasses for the nativity manger, and families enjoy seasonal treats like hot chocolate.

Watch this film to discover more about Peru

Average Monthly Temperatures

High Temp Low Temp

Peru Interactive Map

Click on map markers below to view information about top Peru experiences

Click here to zoom in and out of this map

*Destinations shown on this map are approximations of exact locations

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu was built by the Incas around 1450, and then abandoned in the wake of the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century. For hundreds of years, its existence was known only to local Quechua peasants until a 1911 expedition by the American archaeologist Hiram Bingham brought it to the attention of the world at large. Today it is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

Although it is Peru’s most well-known attraction, it is still shrouded in an aura of mystery. Much of the site is still claimed by the jungle, and archaeologists haven’t decided conclusively what the “lost city” was used for in its heyday; the two most common theories posit that it was either an estate for the Inca emperor, or a sacred religious site for the nobility.

The site is located nearly 8,000 feet above sea level, set between two imposing Andean peaks. The ancient Inca who built it were master architects, fitting together granite stone without mortar to create structures which amazingly still stand today (with the help of vigilant conservationists). Visitors can walk among the ruins, discovering key sites like the Temple of the Sun, and the ritual stone of Intihuatana, and hike to the Sun Gate, for a panoramic view of the site as a whole.

Explore Machu Picchu with O.A.T. on:

Sacred Valley

The Urubamba River Valley, also known as the Sacred Valley, is a region of the Peruvian countryside 10 miles north of Cuzco. Travelers are drawn here for a number of reasons, including hiking, rafting, and visiting the archeological sites and quiet hamlets dotting the landscape.

One of the most popular sites here is Ollantaytambo, where you’ll find the ruins of a mighty citadel, where the Inca bravely fought a successful defense against the invading Spanish armies. The stone-terraced complex also served as a temple, and in modern times, the nearby village is a good place to browse for souvenirs in open-air craft markets.

Nearby Pisac also offers a look at village life in the Sacred Valley, as well as the ruins of another Inca fortress, sitting atop a hill guarding the entrance to the valley. Pisac is an excellent example of the Incas’ innovative terrace farming techniques, which allowed them to cultivate crops at an altitude that would otherwise be inhospitable to agriculture.

Explore the Sacred Valley with O.A.T. on:

Lima

Peru’s capital city is tied strongly to its colonial past. Founded in 1535 by Francisco Pizarro, who named it Ciudad de los Reyes (City of Kings), it served as a colonial stronghold until it was liberated in 1821 during the Peruvian War of Independence. With nearly 10 million people, the modern capital city of Lima is home to almost one third of Peru’s population.

The city today is a mix of old and new, as pre-Columbian buildings stand side by side with stately Spanish colonial homes and Baroque churches along Parisian-style streets. Additionally, the city is continuously expanding as residents construct new shantytowns on the city’s frontiers. Some of Lima’s more famous locales include its UNESCO-recognized historic center, the San Francisco Monastery, Santo Domingo Church, the upscale Miraflores district, and its Baroque cathedral.

Lima is a culinary capital, too. From trendy restaurants serving expensive dishes, to street carts offering more budget-minded options, Lima is a great place to try Peruvian specialties like ceviche, lomo saltado (marinated beef), or for the truly adventurous eater, guinea pig. After your meal, relax and wash it down with a Pisco Sour, Peru’s delectable national drink, made from lime juice, sugar, egg white and Angostura bitters.

Explore Lima with O.A.T. on:

Lake Titicaca

Lake Titicaca is the largest lake in South America, covering an area of more than 3,000 square miles, and is the highest navigable lake in the world, straddling the border between Peru and Bolivia within the Andes mountain range at an altitude of 12,500 feet above sea level.

Its beauty is the stuff of legends, and is a holy place in the Inca religion; in their lore, the god of civilization, Virachocha rose from its depth and willed the sun, moon, and all of creation into existence. Religious and folk traditions of all types are still powerful here; Puno, a city located on the shore of the lake, is considered the folkloric capital of Peru, and is the scene of numerous festivals and celebrations honoring the old indigenous religions, as well as Catholic traditions brought over by the Spanish.

The area was, and still is, inhabited by the indigenous Uros people. Centuries ago, when the Inca encroached upon their lands, they retreated onto the lake itself, constructing entire floating islands out of reeds. Today, around 40 manmade islands still exist where the Uros follow their traditional way of life, centered around fishing and handcrafts.

Explore Lake Titicaca with O.A.T. on:

The Peruvian Amazon Rainforest

Peru’s largest geographical region is also its most sparsely populated. Covering more than 60% of the country’s landmass, there are remote pockets of Peru’s Amazon Rainforest that are populated by indigenous tribes who have never had contact with the outside world. The region’s main city, Iquitos, is tucked so deeply into the jungle that no roads lead there; it can only be reached by air or river.

What Peru’s Amazon Basin lacks in human settlement, it more than makes up for in biodiversity; a single hectare of rainforest here features more species of plant than in any European nation. The rainforest is well-protected by conservationists, but is under continuous threat from oil, logging, and gold mining concerns looking to sack the forest for profit.

Explore Peru's Amazon Rainforest with O.A.T. on:

Featured Reading

Immerse yourself in Peru with this selection of articles, recipes, and more

ARTICLE

Learn more about the stars in the night sky—as seen by the Incas.

ARTICLE

Learn how the ancient Incas engineered their landscape and waterways many years ago.

ARTICLE

Learn how to make a traditional Peruvian ceviche with this recipe.

ARTICLE

Uncover the life of Hiram Bingham, the man credited with discovering the Inca site almost 100 years ago.

RECIPE

Bring the flavors of Peru into your home with this hearty stew recipe.

ARTICLE

Woven into the Quechua heritage is the gift to create hand-crafted baskets, belts, and textiles. Learn about them here.

ARTICLE

True or false: There are no current inhabitants of Machu Picchu. Find out here.

ARTICLE

Peru takes great pride in its native bird: the Andean Condor. Learn about it here.

Stargazing with the Incas

Finding constellations in stone and shadows

by Tom Lepisto, from Dispatches

On clear nights in the Peruvian Andes, the sight of the stars twinkling high above the mountains is dazzling. When you look up from the vicinity of Cuzco or the Sacred Valley, though, you get more than just a beautiful view—you are also seeing the night sky as the Incas did

centuries ago. With no modern city lights to interfere with the view, the stars and the Milky Way gleamed brilliantly for these ancient sky-watchers. They held these celestial visions sacred, observing them carefully for both religious and practical reasons.

The Incas had their own names for groupings of stars like the Pleiades—the cluster we know as the “Seven Sisters,” for the number of stars a keen-eyed observer can count without a telescope. To Incan eyes, this stellar assemblage resembled a handful of seeds, so they called it the Collca, meaning storehouse.

At the latitude of the Sacred Valley, thirteen degrees south of the equator, the Collca/Pleiades cluster drops out of sight below the nighttime horizon every year in April. It reappears in early June, shortly before the winter solstice. This timing, along with other celestial observations, helped farmers to schedule their planting and harvesting, and the return of the Collca to visibility was marked with a sacred ceremony.

The Southern Cross, called Crux in modern astronomy, is another constellation that the Incas found useful. There is no Southern Hemisphere equivalent of the North Star, but the two stars on the long axis of the Southern Cross can be used to draw a line that points due south. In Machu Picchu, near the Intihuatana sun stone in the city’s Sacred District, there is another carved stone that shows the Incas knew this fact well. Its diamond (or kite-like) shape mimics the outline of the Southern Cross, and it is precisely oriented on a north-south axis matching

that of the constellation.

The Incas regarded the Milky Way, which they called Mayu, as a celestial river. For part of each year, Mayu’s orientation in the sky parallels the course of the Vilcanota (Urubamba) River through the Sacred Valley, contributing to the Incan view of objects in the night sky as sacred reflections of their counterparts on the ground.

Another unique feature of Incan astronomy—found in no other culture on Earth—was the recognition of dark constellations in the shadowy parts of the Milky Way. Today, we know these dark areas are caused by non-luminous clouds of dust and gas that obscure the stars beyond them. The Incas saw shapes in these shadows that represented more connections between earth and sky, including Hamp’atu (the Toad), Atoq (the Fox), Yutu (the Tinamou, a partridge-like bird), and Machacuay (the Serpent, viewed positively by the Incas as the god of all things beneath the earth).

Three of the most prominent dark constellations further demonstrate the links the Incas made between worlds above and below. The largest of these shadowshapes is the Llama, with the Baby Llama underneath it and the Shepherd standing watch next to them. The large Llama is the only one of the dark constellations to also include stars, with the bright beacons known today as Alpha and Beta Centauri representing its eyes. In the dark skies of centuries ago, all of these sights were surely awe-inspiring nightly reminders of the Incan worldview. Today, we can still see how these ancient people bound heaven and earth together by putting the Southern Cross on the ground and placing the llamas with their shepherd in the sky.

A good look at the night sky anywhere offers a mind-expanding vista of other worlds. But in the Andean realm of the Incas, it also yields a look deep into the spirit of their culture—whose propensity for stargazing still resonates with anyone who has ever looked upward on a clear night and contemplated our connections to the cosmos.

Finding constellations in stone and shadows

Flow of an Empire

How the Incas engineered their landscape and waterways

by Tom Lepisto, from Dispatches

Think of the work of the Incas, and stone buildings may be the first thing to come to mind. While those rocky edifices are impressive, the ingenuity of their builders extended farther and reshaped vast stretches of the Andean landscape. The largest-scale works left by

the Incas are their agricultural terraces, which turned mountainsides into farmland on a grand scale. Those ancient farmers moved water as well as soil, building canals, channels, and baths, some of which still function after the passage of 500 years.

Like giant stairways with 15-foot-high steps, Incan terraces cover many slopes around their cities, where they provided a convenient food supply. One example is Machu Picchu, where the farming terraces, irrigated by water channeled from a mountain spring, could produce more than enough food to sustain the resident population. The full magnitude of the Incas’ achievements becomes most apparent, though, when you look beyond their most famous city.

British archaeologist Ann Kendall has estimated that Incan terraces and irrigation systems spanned almost 4,000 square miles of the Peruvian Andes in the 1400s. The crops these lands produced fed the empire with staples including corn, potatoes, and quinoa. In the 1970s, Kendall began working with Peruvian farmers to return some Incan irrigation canals near Cuzco to productive use. Reviving ancient techniques holds promise for improving organic agriculture in rural Peru, where the methods used during Inca times remain wellsuited to the Andean environment.

Incan farming terraces were constructed in layers, with stone-and-gravel fill on the bottom for drainage, local soil in the middle, and soil with greater fertility brought up from the lowlands and placed on top. The stone wall fronting each terrace captured warmth from the sun that helped plants grow, and a small canal running the width of the terrace brought water.

The Tipon site south of Cuzco, which may have been a royal estate, offers outstanding examples of such Incan construction. Twelve terraces climb up a mountainside 11,000 feet above sea level, with the difference in elevation giving the lowest terraces a warmer soil temperature than the highest. Because of this, scientists believe Tipon may also have been an agricultural testing station for crops requiring varying degrees of warmth.

Tipon’s waterworks have a beauty beyond their practical use for irrigation. Near the top of the terraces, a ritual fountain sends water plunging down a three-foot drop in four parallel streams, making music that was probably as pleasing to the ears of Inca royalty as it is to ours.

Other ancient sites show how farming terraces were integrated into planned communities. At the southern end of the Sacred Valley, Pisac incorporates terraces, a fortress, temples, and a residential area. The waters of a mountain stream are channeled into a series of individual baths in one part of the site. Ollantaytambo is also remarkable for its blend of stone, water, and terraces. The cobbled streets of the modern town still follow the original Incan layout, with water flowing beside them through ancient channels. Terraces rise steeply up the slope.

Listening to the same rush of water that resounded in such places during Inca times brings their era vividly to life. Most of all, the presence of so much carefully planned construction testifies to the sophisticated level of organization that Incan civilization possessed.

How the Incas engineered their landscape and waterways

Recipe: Peruvian Ceviche

Courtesy of Epicurious

Ingredients:

1/2 pound snapper fillet

2 tablespoons fresh lime juice

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

1 teaspoon minced jalapeño, seeded

1 clove garlic, minced

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/8 teaspoon freshly ground pepper

2 plum (Roma) tomatoes

1/2 small red onion

1 green onion

4 teaspoons chopped fresh cilantro or

flat-leaf parsley

Preparation:

- Cut the snapper into a small dice or strips.

- Combine the lime juice, olive oil, jalapeño, garlic, salt, and pepper in a bowl and whisk to blend well. Add the snapper and toss to coat evenly. Cover and refrigerate for at least 8 hours or up to overnight.

- As close as possible to the time you wish to serve the ceviche, prepare the other vegetables. Peel and seed the tomatoes and cut into neat dice or julienne. Cut the red onion into very thin slices and separate the slices into rings. Cut the green onion, white and green parts, very thinly on the bias.

- Fold the cilantro into the ceviche and mound it on a chilled platter or individual plates. Scatter the tomato, red onion, and green onion on top of the ceviche.

Active Time: 10 minutes

Total Time: 8 hours

Servings: 4 appetizer servings

100 Years Later: Hiram Bingham Machu Picchu

by Andrea Calabretta, from Dispatches

Picchu by Imagine, if you will, a visit to Machu Picchu in the time of Hiram Bingham, around the turn of the century. The site is a five- or six-day hike from Cuzco, and you proceed on foot along the rushing Urubamba River, a headwater of the Amazon, toward the lush green mountains that rise above the river valley, with their peaks hidden in the clouds. Your legs are wrapped in cloth to guard against snakes; the sun is strong, and the air is full of moisture as you climb. Though July is “dry” season, when an infrequent rainstorm comes, it makes the stones in your path slippery, and you cling to vines as you go, dropping to your knees (as Bingham did) to cross at least one flimsy bridge strung between boulders over the rapids. Your final ascent is a precipitous slope, with few handholds, and though you are spurred on by visions of a lost Inca city, you begin to doubt whether you will ever arrive at your destination.

But then, suddenly, perfectly symmetrical agricultural terraces carved into the side of the mountain begin to appear, and farther along, granite houses. As you climb onward, more stone ruins emerge from the mist. Everything is covered in centuries of vegetation, but even so, the spectacular artistry of the cut stone is obvious. As new structures come into view, their architectural lines exquisitely simple and strong, you begin to marvel at the implications of your find: This must be a hidden citadel … one of the “lost cities” of lore … perhaps even the last stronghold of the Inca empire … never discovered by the Spanish … protected by its remote position atop a mountain … and utterly pristine.

Today, a visit to Machu Picchu is different, of course, but no less awe-inspiring than it must have been in Bingham’s day. And it is impossible to visit today without being reminded of the American explorer credited with discovering the Inca site almost 100 years ago, in 1911. One of the PeruRail trains that take you from Cuzco to Aguas Calientes (the tiny town at the foot of Machu Picchu) is known as the Hiram Bingham. The steep and winding road that brings you from Aguas Calientes to the entrance bears his name. And once inside the historic sanctuary, a prominent plaque affixed to a stone wall contains an homage to Hiram Bingham. From first appearances, it’s hard to tell that Peruvians regard Bingham as anything other than a national hero. Certainly there is no sign to indicate he wasn’t the first to discover the Incan citadel, nor any sign that his representation as a swashbuckling adventure hero—seized upon by the international media in the early 1900s—was somewhat … incomplete. But if you dig a little deeper—especially if you ask the locals—the image of handsome Hiram, scholar and explorer, begins to shift. This year marks the 100th anniversary of his “discovery”—a date that is both inspiring posthumous praise and raising difficult questions about the man and his motives.

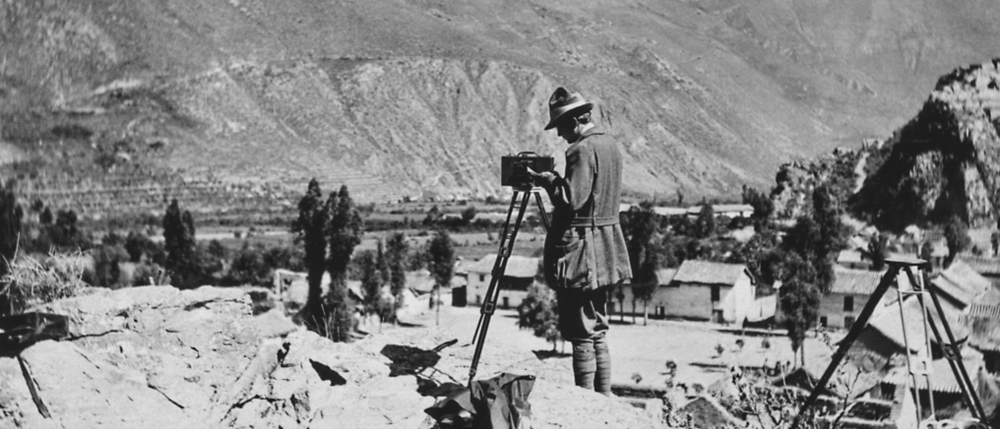

Who was Hiram Bingham? Bingham was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, in 1831, the son and grandson of Protestant missionaries. He attended high school in New England at Phillips Academy at Andover and college at Yale; then obtained a second degree at Berkeley; and finally a PhD at Harvard. Shortly after graduating from Yale, he married Tiffany heiress Alfreda Mitchell, whose inheritance would ultimately help fund his expeditions. Together they had seven sons. Bingham taught courses at Harvard and Princeton before becoming a Yale lecturer in 1907. His subject was South American history—not archaeology or anthropology, as has often been assumed. In fact, Bingham was never an archaeologist and had no formal training in the field. However, a pivotal trip in 1909 focused his interest as a scholar. That year, he attended the Pan American Scientific Congress in Chile. Afterward, he was persuaded by a local official to stop in Peru to explore Choquequirao, a pre-Columbian site. The visit stirred an enthusiasm for seeking out other Inca cities in Peru. He returned to the Andes in 1911 with the Yale Peruvian Expedition.

As director of that expedition, Bingham “found” Machu Picchu on July 24, 1911. His discovery was largely an accident— Bingham was at first headed elsewhere entirely. En route, several Quechua guides, foremost of whom was Melchor Arteaga, steered him the right way. Arteaga led Bingham through dense forest, up the slippery pathways toward the pinnacle of “old mountain” (the English translation of the Quechua “Machu Picchu”). He knew two farmers by the names of Richarte and Alvarez who were living in the vicinity—and were in fact using the agricultural terraces constructed and farmed by the Incas at the height of their empire in the 15th and 16th centuries. After a hard climb of more than an hour, the party arrived at the farmers’ grass huts and paused, taking water and boiled sweet potatoes as refreshments. As Bingham recorded in his notebook, the farmers told Bingham that they “had chosen this eagle’s nest for their home. They said they had found plenty of terraces here on which to grow their crops and they were usually free from undesirable visitors…”

Richarte offered his ten-year-old son as a guide to the foreigner and instructed his son to show Bingham the stone structures near the family’s agricultural plots. Even then, Bingham distrusted the locals and wondered if his climb that day would turn out to be a wild goose chase. Bingham wrote, “I learned that there were more ruins ‘a little farther along.’ In this country one never can tell whether such a report is worthy of credence … Accordingly, I was not unduly excited, nor in a great hurry to move. The heat was still great, the water from the Indian’s spring was cool and delicious, and the rustic wooden bench, hospitably covered immediately after my arrival with a soft, woolen poncho, seemed most comfortable.”

As he followed the child the ruins he found totally exceeded his expectations:“Surprise followed surprise in bewildering succession. I climbed a marvelous stairway of granite blocks, walked along a pampa where the Indians had a small vegetable garden, and came to a clearing in which were two of the finest structures I had ever seen. Not only were there blocks of beautifully grained white granite, the ashlars [squared blocks] were of Cyclopean size, some 10 feet in length and higher than a man. I was spellbound.”

Bingham wondered whether he had located Vilcabamba, the last refuge of the Inca during the Spanish conquest. He also theorized that the site may have been Tampu-Tocco, the birthplace of the Inca Empire, or perhaps a refuge for a religious sect known as the “Virgins of the Sun.” The true purpose of Machu Picchu is still a topic of debate today—scholars contend that it may have served as a fortress, an administrative center, a religious center, a royal estate, or some combination thereof. The most popular theory holds that it was built for the Inca emperor Pachacuti around 1450, at the height of the Inca Empire. Bingham’s pictures and accounts of this vine-covered “lost city” led to two return trips (in 1912 and 1915). The April 1913 issue of National Geographic magazine was entirely devoted to his expeditions in Peru, and suddenly the world was made aware of the Inca ruins once shrouded in mystery. Over three trips, Bingham brought home thousands of artifacts on loan—with the permission of the Peruvian government. Little did they know that the return of those artifacts would one day become mired in controversy.

It was not possible for Bingham to return to Peru following his third trip. His fellow explorers felt left out of the recognition that came from the discovery, which ended any notion of future shared expeditions. And soon, the Peruvian government caught wind of the fact that Bingham was keeping the artifacts he had left with—and he became persona non grata. Instead, he joined the Connecticut National Guard and became a captain. He would go on to organize Military Aeronautics Schools at eight U.S. colleges, and to fly for the U.S. Signal Corps and the Air Service. As Lieutenant Colonel, he oversaw the Air Service flying school in Issoudun, France, in 1920.

Though his South American expeditions were over, no one could accuse Bingham of a sedentary lifestyle—or a lack of self-confidence. He became Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut in 1922 and served one two-year term before running for Governor. He won, but just after the 1924 election, Connecticut’s U.S. Senator died, and Hiram won that seat in a special election. He got up in the morning as Lieutenant Governor, was then sworn in as Governor—delivering the longest inaugural speech in Connecticut history—and presided over a massive ball, then took the train to Washington, where he became a Senator the next morning, making him the only person ever to beLieutenant Governor, Governor, and Senator in 24 hours.

From the moment he arrived in the capital, Bingham was regarded as a show-off. His Senate office was decorated with Peruvian artifacts and pictures of himself with celebrities. He wore expensive clothes, had gleaming silver hair, and was popular with ladies. Soon after taking office in 1924, he translated his cult of personality into a radio show, telling his listeners, “I am still exploring,” and making the capital sound like a grand adventure. He once landed a blimp on the steps of the Capitol to arrive at a committee meeting. Bingham was re-elected in 1926 for a full term. But during the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash, it was revealed that he had paid a lobbyist and allowed him to act as his aide in Finance Committee meetings. At first, a Senate subcommittee deemed this behavior “highly irregular” but did not punish him. However, Bingham then made public pronouncements about having been the victim of a witch hunt, which led to the full Senate’s choosing to formally censure him for demeaning the “good moral and Senatorial ethics”—a criticism not again applied until Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. In his 1932 election bid, Bingham was ousted.

During this bleak period, Bingham’s wife, Alfreda Mitchell, left him because of his longtime affair with another woman, Suzanne Carroll Hill, whom he married in 1937. That same year he was invited back to Peru for the first time. He returned with his second wife for a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Hiram Bingham Highway to Machu Picchu. For a moment at least, it seemed that Peruvian officials had experienced a change of heart. In the 1940s and ’50s, Bingham acted as head of the National Aeronautics Association, a lecturer at U.S. Navy training schools, and Chairman of the Civil Service Commission Loyalty Review Board, an anti-communist body. And though his star was definitely tarnished by past scandals, his fourth book about Machu Picchu, called Lost City of the Incas, was released in 1948 and became a bestseller.

“It seemed almost incredible,” Bingham wrote in 1913, “that this city, only five days’ journey from Cuzco, should have remained so long undescribed and comparatively unknown.” In truth, several men had already laid claim to the discovery of Machu Picchu when Bingham got there. In addition to the two farmers using the terraces, plus Melchor Arteaga, who claimed to have visited the ruins many times himself, foreigners and Peruvians alike had been exploring the site prior to 1911. British missionaries Thomas Payne and Stuart McNairn told relatives of a 1906 visit, five years before Bingham. Peruvian explorers Enrique Palma, Gabino Sanchez, and Agustín Lizarraga are said to have arrived at the site in 1901, five years before the missionaries. The best evidence for their claim is that they left their names carved into a rock with the date “July 14th, 1901.” In his journal, Bingham himself even cites Lizarraga as the ruins’ “discoverer.” Earlier still, several surveyors’ maps from the 1870s include Machu Picchu, marked correctly in its accurate location. The personal maps of the German Augusto Berns, an 1860s entrepreneur and adventurer, also include the so-called lost city.

A little research is all it takes to deduce that Bingham was not the first to discover Machu Picchu—but he did make unique contributions to the site. He was the first to conduct archaeological excavations of the citadel, and he catalogued, mapped, and photographed the ruins in ways not done before. Owing to his connections with organizations like National Geographic, Bingham was also the first to share what he’d found with the international community. He publicized both the ancient city and the Inca people who lived there—including mapping a clear route to the site, the Inca Trail. Thanks to his efforts, Machu Picchu became one of the foremost travel destinations in the world.

Recipe: Peruvian Stew

from Harriet's Corner

While quinoa has only recently become popular in North American cuisine, it has been used by South America’s indigenous population (particularly the Incas) for thousands of years—and is still praised for its nutritional properties. Often called a “supergrain,” quinoa is rich in protein, fiber, magnesium, riboflavin, and manganese. This fall, warm yourself up—and indulge in the many benefits of quinoa—with this recipe for Peruvian quinoa stew.

Ingredients:

1/2 cup quinoa

1 cup water

1 onion, diced

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 Tbsp. vegetable oil

1 celery stalk, chopped

1 carrot, sliced (1/4-inch thick)

1 bell pepper (any color), cut into 1-inch pieces

1 cup zucchini, cubed

2 cups undrained canned tomatoes

2 tsp. ground cumin

1/2 tsp. chili powder (or more, to taste)

1 tsp. ground coriander

1 pinch cayenne (or more, to taste)

1 tsp. dried oregano

1 cup vegetable stock

Salt, to taste

Fresh cilantro, chopped (optional)

Preparation:

- Rinse quinoa well, and place in a pot with water. Cook over medium heat for about 15 minutes, or until soft. Set aside.

- While the quinoa cooks, sauté onions and garlic in oil over medium heat for 5 minutes.

- Add the celery and carrots. Cook for 5 additional minutes, stirring often.

- Add the bell pepper, zucchini, and tomatoes, as well as the cumin, chili powder, coriander, cayenne, and oregano. Cook for a few additional minutes, then stir in vegetable stock. Cover, and simmer for about 15 minutes, until vegetables soften.

- Stir in the cooked quinoa and add salt to taste. Before serving, sprinkle chopped cilantro on top if desired.

Serves: 4

Weaving the Past and Present

The Quechua people of Peru

for O.A.T.

Girls may begin to learn weaving at six—by adulthood, the craft can be almost as natural as breathing.

The cultural landscape of Peru has changed much since Spain first colonized the Inca Empire in 1528. Today, an eclectic blend of colonial traditions mingles with the deep, ancient Inca roots that held fast when the hooves of conquistadors’ horses shook the ground 500 years ago. Despite their strife during this era, the Quechua people—modern descendants of a 2,000-year-old tribe that has seen many empires come and go—are still committed to keeping their heritage alive through art, especially in the mountain village of Chinchero, just outside of Cuzco. Vibrant threads of indigenous tradition still trace a colorful path along the winding roads high into the Andes, where the Quechua keep their ancient heritage alive by—quite literally—weaving the past into the present.

On the famed Inca Royal Road to Chinchero, nested terraces of barley and potato fields rise up toward a windswept plateau in the shadow of the Andes’ Southern Sierra range. Alpacas and llamas abound, and the sky seems endless overlooking the Sacred Valley below. Stone walls give way to steps that curl toward a tall, stucco 17th-century church and open up into the town. In the 1480s, Inca ruler Túpac Yupanqui built a part-time residence here, along with bath houses and temples that lie partly in ruins beside pearly white arches and red clay rooftops constructed by Spanish missionaries.

The weavers of Chinchero

Bright splashes of color dazzle on street corners and courtyards as Chinchero women in red Incan bowler hats and Spanish colonial dresses set up their looms to weave intricate textiles, tapestries, belts, and baskets—just as their ancestors have for two thousand years. Chinchero is known worldwide for these beautiful handcrafts—ornate but delicate, layered and complicated but striking in simplicity, much like the culture that designed them and the women who still create them every day. When the first rays of sunrise light up the partial remains of Túpac’s former palace—now Chincero’s main square—hand-woven baskets of pink, blue, green, and yellow begin to stack up beside the grandmothers sitting cross-legged continue to weave away. Fingers flutter in a rhythm as smooth and complex as the geometric patterns that characterize their artwork. Children linger, in school uniforms and street clothes, to watch the women work. Girls begin learning this ancient tradition as early as six years old—so, by the time they reach adulthood, weaving feels almost as natural as breathing.

Unique blankets for each village

Perhaps the Quechua’s most cherished textile is the hand-woven manta, a thick blanket used for carrying firewood, crops, groceries, or babies on backs. The finest and most intricate mantas are passed down as family heirlooms. Every village has its own unique manta patterns and colors, like flags that symbolize pride in one’s homeland. Mantas from Chinchero can be distinguished by their blocks of solid color—called pampas, which are large swaths of untilled land—framed by elaborate linework, which represents civilization and agriculture. When looking at Quechua weavings, it’s easy to see how the world around them influenced their art—and dream of what life was like for them before the conquistadors arrived.

It’s here that the Peruvian spirit is most alive, vibrant as the most ornate basket or manta: Despite all the change and adversity of the imperialist era and beyond, the locals have held fast to their traditions. By weaving ancient Incan and colonial Spanish influences together with brilliant color, they’ve created a dazzling cultural tapestry all their own.

The Quechua people of Peru

5 Myths of Machu Picchu Debunked

by Zack Gross, for O.A.T.

1. Machu Picchu is the legendary “Lost City” of the Incas

Hiram Bingham III stumbled upon Machu Picchu in pursuit of Vilcabamba, the last Inca city to fall to the Spanish conquistadores. It’s evident from his writings that when he saw it, he was convinced he had finally discovered the “lost city.” Nestled between the Andes Mountains and seemingly floating among the clouds, it’s no wonder the mystical remains of Machu Picchu seemed to be the culmination of his quest. If you’ve fallen prey to this common misconception, please find solace in the fact that Hiram Bingham did too. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t be until after Bingham died that his error would come to light. It is now widely believed that the true lost city of Vilcabamba was located at a site called Espiritu Pampa, which Bingham also visited, but didn’t attribute as much importance to in his writings.

2. You can see all of the ruins

We’ve all heard the expression “just the tip of the iceberg.” Well, the same could be said about what you’ll see of Machu Picchu. Surprisingly, there’s much more to these ruins than meets the eye, as a majority of the Inca’s handwork actually resides under the ground. Before the wheel arrived in the New World, and long before steel and concrete became the blood and bones of construction work, the Inca people built the walls and terraces of Machu Picchu with only stones. Without even using mortar, they built an entire complex of buildings with stones cut so perfectly and placed so closely together that the cracks between them can’t even be penetrated by a credit card. Inching up to the edges of cliffs overlooking the Urubamba River, the stone city that stretches boldly across this high ridge in the Andes is actually perched above an underground irrigation system and building foundations. The underground foundations of Machu Picchu are so strong, in fact, that when earthquakes hit, the perfectly placed stones are said to “dance” and then fall right back into place.

3. There are no current inhabitants of Machu Picchu

Built over 500 years ago, and mysteriously abandoned in the early 16th century, Machu Picchu hasn’t had any human inhabitants for a long time. However, there are quite a few animals that still call this incredible place home. Not only are there plenty of llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas roaming the ruins—“nature’s lawn mowers,” as the locals lovingly call them—there are also some rare and endangered species dwelling in the surrounding tropical rain forest. South America’s only native bear—the spectacled bear—resides here, along with the world’s smallest species of deer (the pudu), and ocelots, to name a few.

4. Machu Picchu was originally a nunnery or convent

When Bingham dug up skeletons at Machu Picchu, a leading expert at the time told him that the remains were mostly female. Based on this finding, Bingham surmised that the city was built as a nunnery or convent. He even went on to suggest that it may have been home to the Virgins of the Sun, a sect of Inca women who lived in religious compounds. However, it was later found—upon further examination of the remains—that there was actually a relatively balanced mix of male and female inhabitants, and that the characteristically small stature of the Inca people probably misled early 20th-century scientists. Interestingly enough, their small physiques are actually a manifestation of the Inca’s deep-rooted connections to life in the mountains. Over centuries of living high in the Andes, they developed a shorter stature, larger lungs, and more red-blood cells, all of which aid in respiration and circulation at high altitudes.

5. Your trip to Machu Picchu can wait

If Machu Picchu has always been one of your dream destinations, don’t wait! There has never been a better time to go, as new rules and restrictions are under discussion that would limit the impact of tourism on the spectacular ruins. The Ministry of Culture in Cusco has, for example, considered limiting the number of people who can visit each day, and the amount of time you are permitted to spend in each area of the ruins. While we support any decision that will help preserve this wonder of the world, we urge you to go there soon to maximize the ease of exploration and your enjoyment of the ruins on your own terms.

The Andean Condor

How an ancient symbol is flying high again

by David Valdes Greenwood, from Dispatches

In the plaintive original lyrics of El Condor Pasa, the most famous Peruvian song of all time, the singer pleads,

“Wait for me in Cuzco, in the main plaza!

Wait for me in Cuzco, in the main plaza,

So we can go together to walk in Machu Picchu.”

For all the longing in every line, the object of the entreaties is not the singer’s beloved—or, for that matter, even human. The subject of the ballad is the Andean Condor itself, the mighty bird which has been a symbol of Peruvian culture since the time of the Inca. And the singer, a Quechua mine worker in the city, is pleading with the condor to fly him back to the Andes.

For Peru, the condor represents legend, history, nature, and tradition all in one. Believed by the earliest Andeans to be the emissary of the Sun God and the ruler of the air, the bird was immortalized in the Temple of the Condor at Machu Picchu. There, the ingenious builders added stone blocks to a natural outcropping to replicate wings that rose above a carved condor head with a beak and ruffled collar. To this day, wherever you travel throughout the land of the Incas, the bird’s image is represented in statuary, artwork, graphics, and even textiles. From coffee shops to a regional airline, the logo of a condor is one way of proclaiming that a business is truly Peruvian.

Despite being so well-loved, the species was facing near extinction by the late 20th century, its numbers having dwindled from hunting and loss of habitat. In 1970, the breed was placed on the international “endangered species” list. In the 40 years since, Peru and its neighboring nations have strengthened environmental laws, implemented education plans to help their citizens better understand the value of preservation, and introduced captive-born condors into the wild. As a result, the species has stabilized in numbers to the point where it is currently listed as “Near Threatened,” one step up from “Vulnerable,” which in turn is an improvement over endangered.

When you see a condor up close—or even soaring high overhead— it’s hard to imagine such a creature ever seeming vulnerable.

Its sheer physical impressiveness makes it rare among its avian peers: Weighing up to 35 pounds, it boasts a wingspan of ten feet. How big is that? Imagine a bird with a body the size of a four-year-old boy and wings that unfurled beyond the width of a school bus. Not surprisingly, the Andean Condor one of the largest flying birds on Earth.

It is also among the most enigmatic. Because a condor has no voice box, it never sings or squawks its feelings. Playing the strong, silent type, the vulture only betrays its emotions when its face flushes. A condor likes to keep its face meticulously clean, so when strong emotions send blood rushing to its cheeks, the thin skin darkens noticeably. This is as close as a condor gets to making a fuss.

The silence of a condor extends to how it flies. Once airborne, it can remain aloft without any noisy flapping, carried along for miles on thermal currents of air, like a hang glider. This combination of songlessness and stillness in flight deepens the mystique of the breed.

While the condor always plays it cool, the people of Peru don’t hold back. They unabashedly love their soaring symbol, just as their ancestors did. And with the condor population rebounding, it seems they’ll be singing its praises for years to come.

How an ancient symbol is flying high again

Traveler Photos & Videos

View photos and videos submitted by fellow travelers from our Peru adventures. Share your own travel photos »